Discretionary Effort: a DIY Guide

Elinor Rebeiro

A key point of discretionary effort is that by definition it is discretionary. As a leader you can't demand it - you have to earn it. As soon as you set it as a goal you are essentially expecting people to work for free.

According to Engage for Success "Employee engagement cannot be achieved by a mechanistic approach which tries to extract discretionary effort by manipulating employees’ commitment and emotions. Employees see through such attempts very quickly and can become cynical and disillusioned."

The question becomes why do people sometimes choose to give more of themselves than is asked for in their job description? It is about care and the relationship they have with the people they work for and work with.

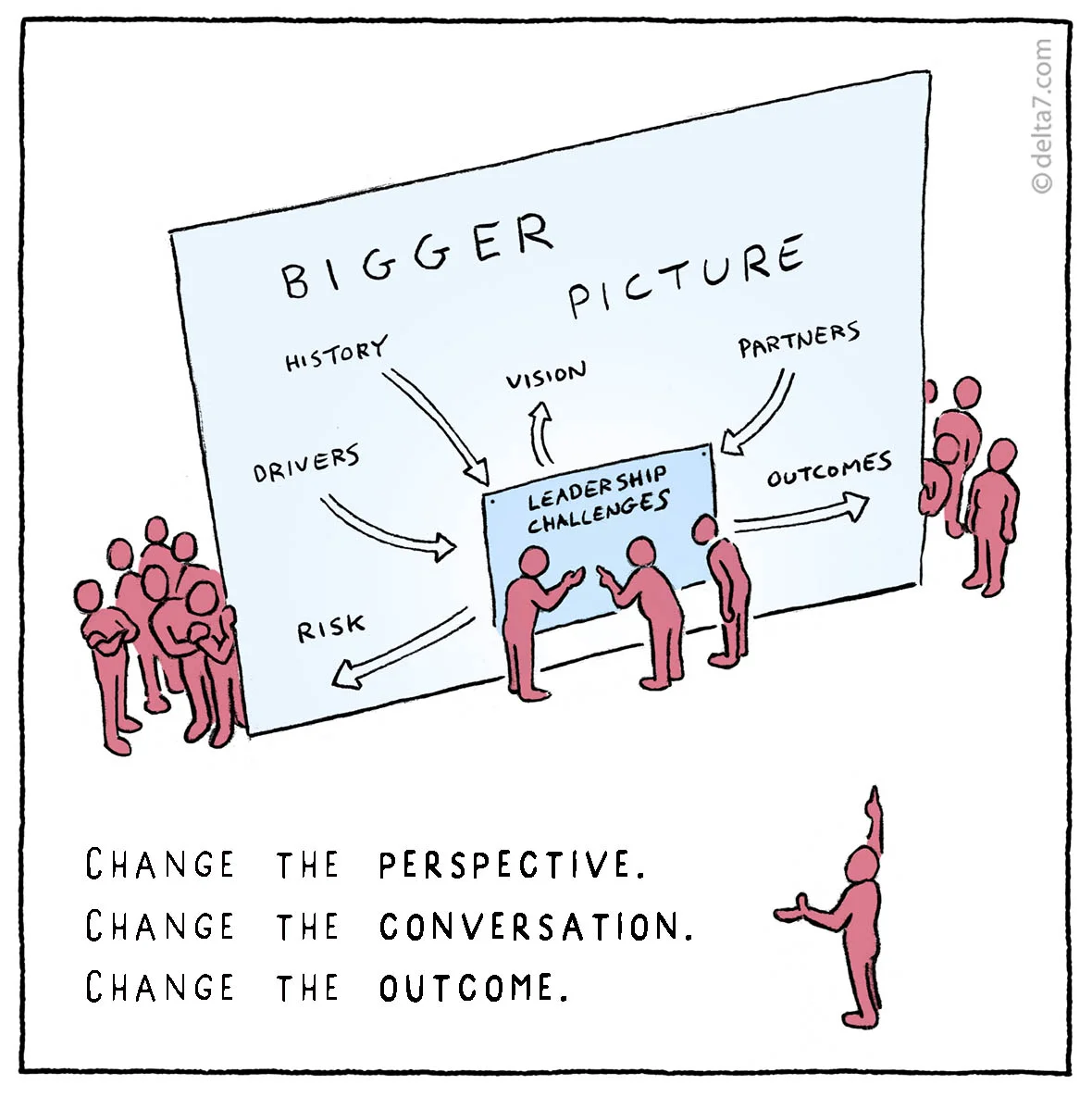

From a management perspective it is clear that the challenges in the world are requiring organisations to respond in a different way; that managers can't succeed without employee discretionary effort. The danger is that as soon as you identify discretionary effort as essential you have to consider what the implications of this are when heard by employees.

The answer is care and relationships. How we take care of each other, how we relate to those people who we spend more time with than our own families will always impact the level of commitment and care you will receive back. This can be the only motivation - otherwise the care becomes false and people will see through that very quickly.

The most amazing example of discretionary effort I have witnessed is within our wonderful (and under cared for) National Health Service. Staff choosing not to go home until they can find a bed for their patients. Preparing food and drinks for them and caring for them in ways that are not asked for or expected. And the reason they do this? Their conscience won't let them do anything else. With the challenges of resourcing and capacity issues facing the NHS it is this quality of care that keeps it functioning.

My experience

When I first became a manager I was young - a lot younger than some of those I was managing. I had a steep learning curve ahead of me and I failed - a lot - until I realised that I had to earn their respect, trust and care. I tried often to short circuit the process; find a quick way to get people to follow me, manipulate them, guilt them into staying later. I always thanked them for their effort, but that really wasn't enough.

I remember one phrase I used a lot when I was talking about work was 'They don't need to like me. I don't need friends, I need employees that do their job.' I was honestly kidding myself. This was my defence when I had to be tough, but what I realised was that actually they did have to like me and I had to like them, but more than that: we had to care for each other. This was the first time we functioned well as a team, we had each other's backs and we did what needed to be done for each other. I stopped having to think about asking for more because we all gave more where we could and they saw me doing it as well. We were in it together and that's what made it work. My new phrase when I thought about work was 'don't ask others to do something you aren't prepared to do yourself.'